About the Esso Salons of Young Artists

What were the Esso Salons of Young Artists?

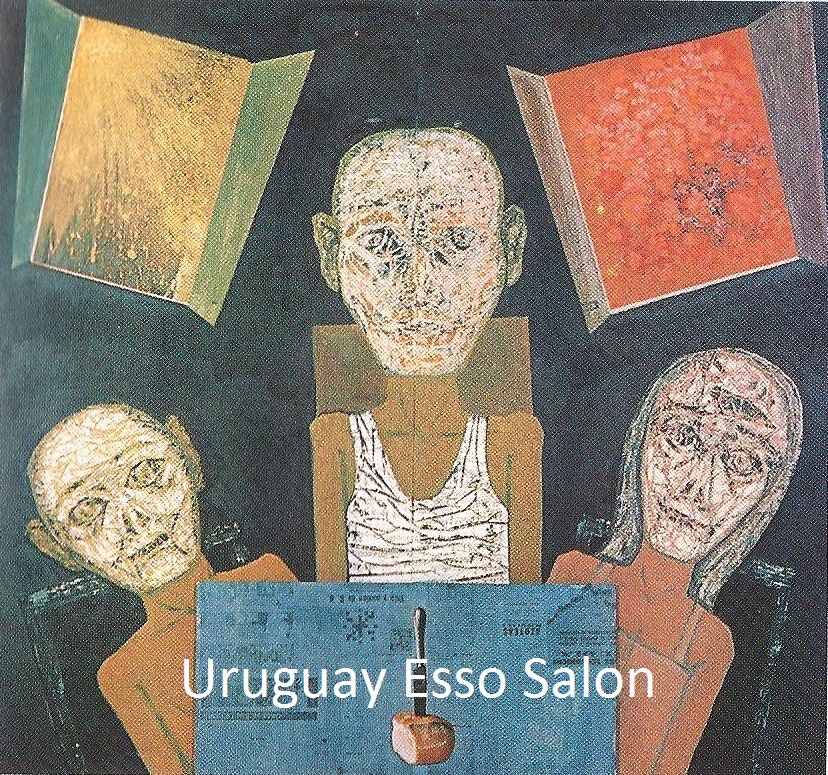

From July 1964 to April 1965, the Esso (Standard Oil) Company and the Organization of American States (OAS), a hemispheric pact started during the cold war, sponsored a series of juried art competitions in Latin American countries, known as the Esso Salons for Young Artists.[i] Artists aged 40 and under participated, winning monetary prizes and broad exposure for their work. The Director of the Visual Arts of the Pan American Union (PAU), the headquarters of the OAS, José Gómez Sicre, organized the Salons in 18 countries and Puerto Rico, specifically where Esso’s affiliates were located. Hundreds of artists submitted up to three works each in hopes of garnering first or second prize in painting or sculpture. Each country was given approximately $3,500 dollars by Esso affiliates to split amongst the prize winners.[ii] These prize-winning pieces moved on to compete in the culminating Salon held at the galleries of the Pan American Union in Washington, D.C., April 21-23, 1965. Along with a chance to secure the Grand Prize in Painting or Sculpture, artists could win a $2,000 prize at the national level.[iii] The Washington, D.C. Salon took place alongside several other hemispheric events, including the InterAmerican Music Festival, a series of concerts that included works composed by U.S. and Latin American composers for the occasion, the Esso Film Festival, where guests viewed various films produced in Latin American along with art educational films produced by the Visual Arts Department of the PAU, and a Roundtable for the Arts, attended by arts scholars from both continents discussing the “role of young people in the arts.”[iv] After the final festivities in, the artworks remained on view to the public through May 15, and then traveled to the IBM Gallery in New York City.[v] IBM had a manufacturing plant in Argentina and, like Esso, supported international art in the 1960’s.[vi]

The Washington D.C. Salon at the Pan American Union Galleries was truly a cosmopolitan and fashionable affair.  Widely publicized, the event

Widely publicized, the event

commenced with a private gala premiere on the evening of April 21, 1965, attended by the top echelon of the D.C. social and diplomatic scene, including First Lady Ladybird Johnson, the Secretary General of the OAS, His Excellency Dr. Jose A. Mora and wife, the President of Standard Oil Company, Mr. J.K. Jamieson, and the Assistant Secretary of State for Education and Cultural Affairs Harry C. McPherson and his wife.[vii]

commenced with a private gala premiere on the evening of April 21, 1965, attended by the top echelon of the D.C. social and diplomatic scene, including First Lady Ladybird Johnson, the Secretary General of the OAS, His Excellency Dr. Jose A. Mora and wife, the President of Standard Oil Company, Mr. J.K. Jamieson, and the Assistant Secretary of State for Education and Cultural Affairs Harry C. McPherson and his wife.[vii]

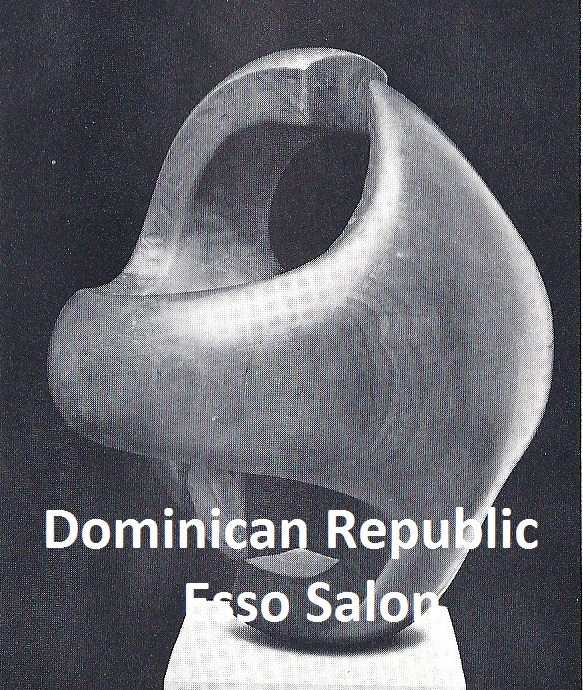

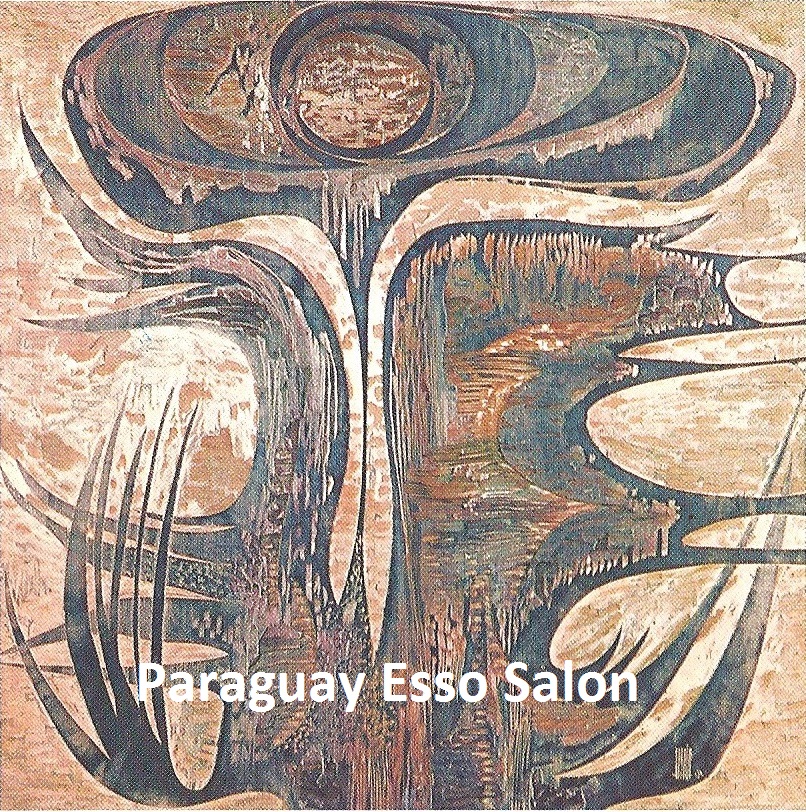

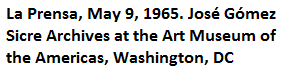

The Salon opened for public viewing the next day. The jury, consisting of top art experts from the United States - Alfred H. Barr, Director of Museum Collections at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City; Thomas Messer, Director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City; and Gustave von Groschwitz, Director of the Institute of Art at the Carnegie Institute - met to decide the winners on the morning of April 23.[viii] No Latin Americans acted as jurors in this Salon, though there was always at least one local juror represented at each of the individual country salons. The winners of this Salon, Rogelio Polesello, a painter from Argentina, and Hermann Guggiari, a Paraguayan sculptor, were flown to the United States for an awards dinner on April 29, 1965.[ix]

The Salon opened for public viewing the next day. The jury, consisting of top art experts from the United States - Alfred H. Barr, Director of Museum Collections at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City; Thomas Messer, Director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City; and Gustave von Groschwitz, Director of the Institute of Art at the Carnegie Institute - met to decide the winners on the morning of April 23.[viii] No Latin Americans acted as jurors in this Salon, though there was always at least one local juror represented at each of the individual country salons. The winners of this Salon, Rogelio Polesello, a painter from Argentina, and Hermann Guggiari, a Paraguayan sculptor, were flown to the United States for an awards dinner on April 29, 1965.[ix]

What was the purpose of the Esso Salons of Young Artists?

The purpose Salons had multi-faceted purposes. The entire program was planned to coincide with Pan American Week and to celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the Inter-American System, an agreement between the countries of the OAS and United States on basic human rights. [x] A March 10, 1965 statement released by the Pan American Union declared its official purpose: “to bring to the United States, and later to other cities of the world, this new genre of art, unique, brilliantly colorful, combining the best of the Latin tradition, but sharply attuned to the new and exciting revolutionary art forms.”[xi] But, as in the case of many government affiliated events, there were more than just purely aesthetic aims behind the Esso Salons.

The Esso Company sought to improve its public image through the Salons of Young Artists. Standard Oil of New York, under the brand name Esso, had been involved in the exploration, production, refining, and marketing of oil in the 17 Latin American countries participating in the Salons from as early as 1912.[xii] Standard Oil is now known as Exxon Mobile. Esso got the ball rolling for the Salons when it approached Gómez Sicre to organize and co-sponsor the events under the umbrella of the OAS. The company and its affiliates promoted cultural programs for years as part of its public relations campaign in Latin America, a thriving business region for the U.S.-based company. Esso was one of a handful of international companies that provided a majority of the oil products to Latin America, and was often accused of engaging in capitalist exploitation that left the host nation at its mercy. In Chile, for example, Esso and Shell companies owned 100% of the oil market starting in 1917 and were involved in price-fixing in 1939, simultaneously skyrocketing prices by 25%.[xiii] In light of such negative publicity, it was in Esso’s best interest to promote an image of “corporate citizenship” in Latin America in which its affiliates sought to improve the “developing” countries in which they did business.[xiv]

Gómez Sicre highlights Esso’s role in the Salons in the preface of the Washington D.C. Salon: “Of similar significance was the fact that it was private industry – the capitalistic initiative of the free world – that was thus seeking to foster the things of the spirit by an undertaking of broad cultural repercussion.”[xv] This type of corporate sponsorship was sanctioned by the highest U.S. political representative attending the Salon. In her letter accepting an invitation to the premiere, First Lady Ladybird Johnson stated, “It is heartening also that the Pan American Union and a private company have joined forces to make this Festival possible, for it is through this type of dedicated partnership that our Hemisphere will grow in strength and freedom.”[xvi]

First Lady Johnson eloquently summed up the goals of the United States government in promoting the Esso Salons, a prime example of an event aimed at bringing North and South America closer together. After the Cuban Revolution in 1959, there was widespread admiration for Castro and his brand of communism in Latin America. As Castro unleashed a tirade of anti-U.S. imperialistic rhetoric in the press - the U.S. government began to fear that the rest of Latin America would follow Cuba’s example and fall to communism. The Alliance for Progress continued by President Lyndon B. Johnson through the 1960s, constituted a “large-scale U.S. initiated development program intended to compete with the Cuban Revolution for the hearts and minds of Latin Americans.”[xvii] The Organization of American States became a main conduit for PanAmerican promotional projects, including those involving cultural development, such as in the visual arts. The Esso Salons were ideally positioned, as a press release stated, “to help build close cultural ties between the United States and its talented neighbors of this hemisphere.”[xviii]

What was the legacy of the Esso Salons?

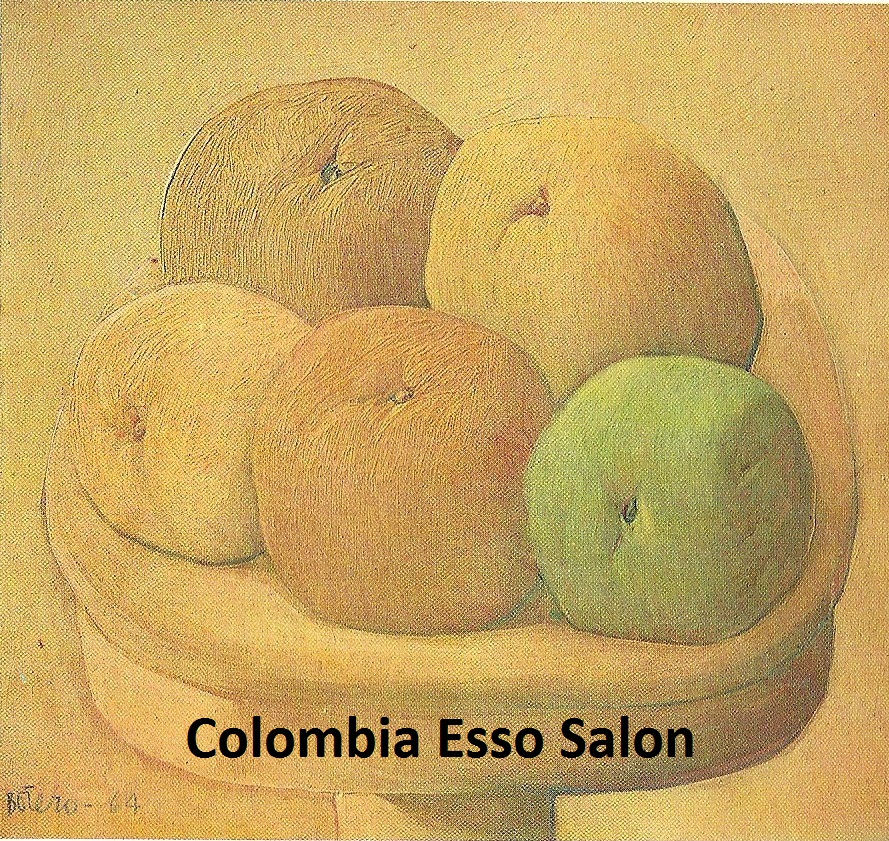

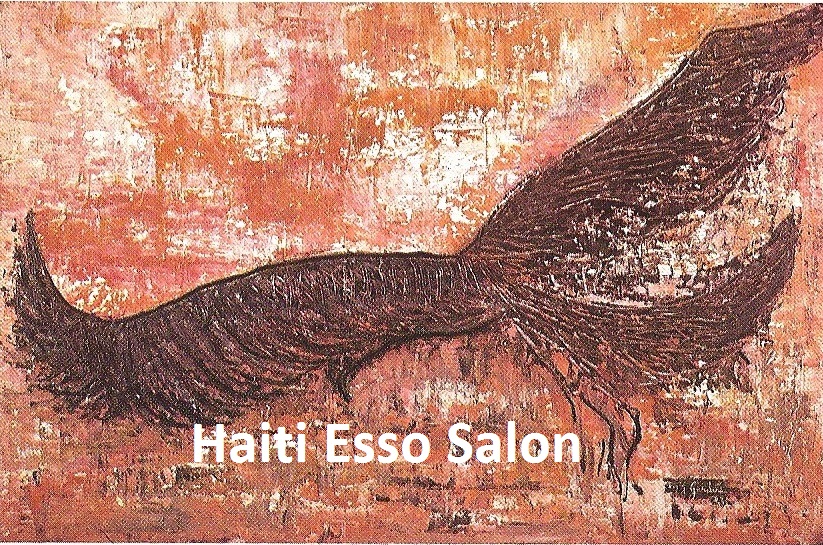

The artists and host countries certainly benefited from the Salons. Many winning artists have since gained critical and market success, such as Fernando Botero, whose works have sold for over $1 million, and Fernando de Szyszlo. [xix]The selection of other artists like Olga Albizu, for instance, have taken decades to be validated by the artworld. But without question, many of these artists already had blossoming careers and had been part of exhibits in major museums throughout the world prior to the Salons.[xx] The exposure given by the Salons could only further these artists’ careers, however, and some relatively unknown artists, such as the self-taught Mortes Merisier from Haiti, emerged through the competitions.[xxi] The publicity continued as the artworks featured in the Washington D.C. Salon traveled to New York City.[xxii] Although the winners gained recognition and monetary prizes, the countries themselves arguably recieved the largest boost from the Salons. Gómez Sicre had maintained a vision of art centers throughout Latin America on par with recognized centers in New York and London.[xxiii] He used the Esso Salons as a strategic vehicle to further this goal, laying the infrastructure for these “other” capitals of art. “In the wake of the Colombian Esso Salon” as Clair Fox has observed, Gómez Sicre supported the foundation of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogota and the Instituto de Arte Moderno de Cartagena with financial support from International Petroleum, Colombia’s Standard Oil affiliate.”[xxiv] Though this initial groundwork was laid, the Latin American artistic capitals have yet to be fully realized as Gómez Sicre envisioned.

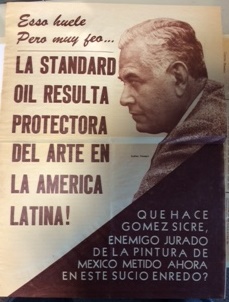

The Esso Salons were not without controversy. The role of Esso, seen by some Latin Americans as a symbol of North American capitalism and neocolonial exploitation as facilitated by Gómez Sicre, incited protests, especially in Mexico.[xxv]

Esso took ownership of the winning art after the Salons – plausibly, to streamline the many complicated tariff and legal issues involved with moving the art out of Latin American countries, but also to the benefit of its permanent collection.[xxvi] The level of compensation, moreover, did not meet the expectations of the artist. In a letter to Gómez Sicre, Guatemalan painter Rudolfo Abularach complained about the amount paid for his work, though acknowledging gratitude for the exposure.[xxvii] The actual amounts that may changed hands between Esso and the artists is unknown, although according to Salon rules, the works belonged entirely to Esso after the competition, with no mention made of compensation.[xxviii]

Esso took ownership of the winning art after the Salons – plausibly, to streamline the many complicated tariff and legal issues involved with moving the art out of Latin American countries, but also to the benefit of its permanent collection.[xxvi] The level of compensation, moreover, did not meet the expectations of the artist. In a letter to Gómez Sicre, Guatemalan painter Rudolfo Abularach complained about the amount paid for his work, though acknowledging gratitude for the exposure.[xxvii] The actual amounts that may changed hands between Esso and the artists is unknown, although according to Salon rules, the works belonged entirely to Esso after the competition, with no mention made of compensation.[xxviii]

The judging of the Salons itself was further called out for its personal and ideological biases. Though Gómez Sicre stated in the Preface to the Washington, D.C. program that “every trend in present-day art was represented by the works submitted for evaluation,” he favored a generally abstract, unpoliticized art that many felt was unrepresentative. A Colombian art critic, Luciano Jaramillo, proclaimed, “En pocas palabras: son pinturas bonitas y elegantes, pero sin contenido colombiano ni americano.”[xxix] (In a few words: they are beautiful and elegant paintings but without Colombian or American content.) Artists in Mexico agreed that the jury, which included Gómez Sicre, was “biased in favor of abstraction” and that Gómez Sicre held a grudge against Mexican painting. Gómez Sicre openly opposed the famed Mexican muralists, such as Diego Rivera and David Siquieros, for what he considered overly left-leaning, political works.[xxx] Mexican artists additionally accused their jury of nepotism when a prize for painting was awarded to Fernando Garcia Ponce, the brother of juror Juan Garcia Ponce. Fifteen of the participating artists signed a letter of protest to the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes.[xxxi] Despite the challenge, no change was made to the winning selections in Mexico.[xxxii] No other such egregious accusations of bias appeared in the press coverage of the other Salons.

Despite hidden agendas and ongoing contention between Esso, the PAU and the artists themselves, the Esso Salons achieved a level of success beyond the merely ephemeral. Measurable results were seen in the growing arts infrastructure of several countries as they ramped up in preparation for the Salons. “For those concerned with the lasting values,” Gómez Sicre reflected, “the most significant lesson to be derived is that, with freedom of expression, with liberty to accept or reject direction, art continues its forward progress in the Americas. In the best tradition of the past, it confidently awaits the challenge of the future.”[xxxiii]

Click below to explore the Esso Salons